|

| "Fore! is essentially a continuation of Sports but with an even more professional sheen." |

dir: Mary Harron

writer: Mary Harron, Guinevere Turner

author: Bret Easton Ellis

Books and movies are separate entities, and it is generally unfair to use a book to critique a movie, especially if that movie had otherwise hewed close to the themes of the book. For instance, Adaptation. chose to make grave changes to its book The Orchid Thief and ended up staying closer to the themes of the novel. And, then there are the instances where the movie hews close to the narrative of the book, but completely changes everything, like the relation to Dr. Strangelove and Red Alert.

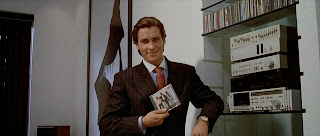

So, while it is fair to separate the two, it is also fair to examine how they are different. With American Psycho, the relationship is far more complex than any of the other relations mentioned so far because American Psycho the novel has so many different layers it needs to be read at.

The Novel (1st pass)

"I was writing about a society in which the surface became the only thing. Everything was surface -- food, clothes -- that is what defined people. So, I wrote a book that is all surface action: no narrative, no characters to latch onto, flat, endlessly repetitive. I used comedy to get at the absolute banality of the violence of a perverse decade. Look, it's a very annoying book. But that is how, as a writer, I took in those years." - Bret Easton Ellis, New York Times, March 3, 1991

Let's start with a basic rule. Bret Easton Ellis is a provocateur. But, he's also oblique. He will punch you in the face in order to demonstrate the risks of plastic surgery. That said, the first time one reads the rather excessive American Psycho, one takes it at face value. I mean, it's really hard to see the comments on plastic surgery while you're in blinding pain, right?

At the time of American Psycho, Bret Easton Ellis was living a lifestyle very similar to Patrick Bateman, and very publicly at that too. He had been lumped in as a bad boy of writing, and as part of a literary brat pack that included Jay McInerney and Tama Janowitz. All of whom were on the East Coast, frequently associated with New York City, and always talking about drugs and sex. They were also living the lifestyle they seemed to be promoting. Or at least putting on the airs that they did. They also used real life people in their novels, either directly or indirectly.

As such, it is very easy to read American Psycho as a satire and as an indulgence of that lifestyle. Ellis' main protagonists, anti-heroes though they may be, are generally read as stand-ins for Ellis himself. His novels have been seen as somewhat auto-biographical, and also gloating in the excesses he presented. The criticisms for The Rules of Attraction, for instance, were largely that the protagonists were completely vacant and seemed to be happy and angry without any real reason as to why.

On the face of American Psycho, Ellis is dissecting the behavioral patterns of Patrick Bateman, a Wall Street rich dude who attempts to be as cold as they come to the point of being a serial killer. He holds a bloodthirsty contempt for women, and also hates anybody who is either more successful than him, or stupider than him.

American Psycho, the novel, is written in the first person. Patrick Bateman is our narrator and host for the book which clocks in at a solid 399 pages in my paperback edition. The only time the novel isn't personal is when Patrick Bateman is espousing on the wonders of Genesis, Whitney Houston, or Huey Lewis & and The News in multi-page dissections of their discography. The remainder of the novel is spent following around Patrick Bateman as he tries to hobnob with the cool, rich and powerful kids. He also spends a lot of time raping, violating, torturing, or brutally murdering people, mostly women. And, in between, he lists name brands of every piece of clothing he and everybody else is wearing, while also obsessing over Donald Trump.

Did I mention it's a comedy? Ellis will spend a lot of time espousing on silly items such as business cards, and going over trite and inane dialogue, or over the minute details of life. "Evelyn is talking but I'm not listening. Her dialogue overlaps her own dialogue. Her mouth is moving, but I'm not hearing anything and I can't listen, I can't really concentrate, since my rabbit has been cut to look...just...like...a...star!"

The novel is celebrating the things it is satirizing. Based somewhat in reality, and somewhat on actual experiences, the novel is easily read as Ellis saying "I got mine bitches!" while also satirizing the actual excess of the novel. Since Bateman is writing about his enthusiasm for all the material goods, the cocaine, the terrible music (like Katrina and the Waves), and everything else status, we are led to believe that he is actually in love with all of this. And, when he switches over into murder, it is equally as rapturous.

Patrick is posing throughout the novel. He's successful at it, and he is dating the right girl, and going to the right clubs and wearing the right clothes. But, he has a murderous side that slowly and increasingly comes out as the book moves on. Ellis will start going on for pages writing mundanely about the brutal aspects of whatever torture/murder Bateman is inflicting on his victims. And, it seems like Bateman is reveling more honestly in the murders than he is in the '80s excess. It seems like violence is honest, while the lifestyle isn't.

The first pass of American Psycho is like reading the novel version of Man Bites Dog, about a rather charming serial killer who is able to pass in American society. It's as horrific as Man Bites Dog, if not more so, including the censored version. But, Bateman is able to pass in society, and is frequently chased by his own mentality.

There are hints that, as the violence gets more extreme, and Bateman claims he is increasingly losing his mind, the book isn't real. But, by the time you get to that point, you're already bought in on the reality of the novel and believe that Bateman is actually a psychotic serial killer who is also a Wall Street Executive. When the novel came out, there was debate over whether the murders were real or in his head, without any real debate about it.

On this surface, American Psycho is a sufficient satire and celebration of '80s excess, and is also about the brutality that some men can commit on everyday people. Because, it's not just women that Bateman kills; his first victim is a homeless guy and his dog. And, on this level, its also a cutting look into what it takes to get ahead in America. You have to be bold, you have to fit in but stand out at fitting in. You have to do the right things, look the right way, and be the right person. You can have your inner life, but you have to be the right person on the outside.

This satire of '80s excess was also released in 1991, one year after Paris is Burning, this was all about the excess of 80s culture. American Psycho displayed the full-on fetishization of the high powered executive in Manhattan that Paris is Burning was also emulating in the poorer subcultures of the Bronx drag scene. American Psycho was all about hardbodies, models, and pop culture in much of the same manners as Paris is Burning. Taken together, both American Psycho and Paris is Burning show, full-on, the materialistic wasteland that the 1980s had become. Add in Tom Wolfe's The Bonfire of the Vanities, and you have the complete picture for the self-important grandeur of the businessman that would eventually lead to the frequent rises and falls in the American economy.

The Movie (1st pass)

"On a literal level, Bateman would never have gotten away with it. But, that is precisely the point of the novel - and the film. No one suspects Bateman of being a monster because his externals fit so perfectly into his social landscape." - Mary Harron, production notes from original DVD

Mary Harron and Guinevere Turner had a history coming into this movie. Turner had gotten her first start as a writer on Rose Troche's Go Fish, a seminal lesbian film out of the New Queer Cinema movement. Mary Harron and Turner both teamed up on I Shot Andy Warhol, Harron's first movie. I Shot Andy Warhol was about Valerie Solanas, feminist author of the SCUM manifesto and, also, lover and shooter of Andy Warhol. The SCUM Manifesto was a screed that talked about a world without men, and was scathing in its critique of a male-dominated world in the 1960s.

When American Psycho the film came out, Harron was quoted in the press saying that American Psycho is a horror movie, and all of the fear of American Psycho is fear as a woman. Indeed, much of American Psycho the novel is about how Bateman doesn't respect a single woman, and tortured them throughout the novel.

As such, American Psycho, the film, is pointedly a woman's take on a male protagonist as originated by a male author. Turner was none too happy with the novel, and actually hates it in real life. She had to do it for money because a different project she was set to work on fell through. Regardless of attitude towards source material, both Turner and Harron made the film as if Bateman was a representative of the American power male.

The film of American Psycho has a lot in common with Tom Wolfe's novel The Bonfire of the Vanities, and it's depiction of the male power figure in the form of Sherman McCoy. Bateman and McCoy share wealth, a love of mistresses, and a heightened egomania that constantly occurs. Bateman and McCoy also are paranoid about getting caught and frequently stress about the consequences to their behavior.

Harron's Bateman is generic, interchangeable, and generally just perceived as one of them. She occasionally has people call Bateman out as a loser or a geek, but mainly behind Bateman's back as Bateman does about everybody else behind their back. The gossip in the film is constant and sharply aimed at everybody.

Harron's Bateman is also an actual serial killer up until the last act, where she gives surreality a twist and starts to make it a "did he or didn't he" questionable scenario. By keeping a large portion of the violence off screen (the unrated version takes out moments of sex, but not of violence), Harron is keeping us with Bateman all the time, and heightening the fear of the women. Indeed, one of the pure horror scenes that she recreates is of a prostitute being chased by Bateman clad only in white running shoes, streaked in blood, and chasing her through the building with a chainsaw, ultimately dropping it on the woman's head while laughing.

This is a horror for women. It is a symbol of phallic male power. While its reality is questioned by the stylization, neither Harron nor Turner delve into why the character of Bateman. They just merely assume he's either crazy or he's a misogynistic dick who kills either for power or to display power. Or, at least that's how they construct the movie for the most part. The one time that Bateman kills after being humiliated, he kills the bully of that target who was stating his ability to get into Dorsia, a restaurant that is also a symbol of status.

As such, Harron has created her own movie based on a surface reaction to the novel, especially a first time reading it. And, while it is a funny piece of comedy horror and satire that skewers the '80s and also the cult of male conformity and machismo, Harron ultimately misses the point of the novel.

The Novel (2nd pass)

"American Psycho came out of a place of a place of severe alienation, loneliness and self-loathing. I was pursuing a life that I knew was bullshit, and yet I couldn't stop myself from doing it." - Bret Easton Ellis, Paris Review, Spring 2012

Earlier, I had mentioned that Bret Easton Ellis is intrinsically tied to his novels. He is practically his own model. Later, Ellis would parody this idea in Lunar Park, which was a self-referential book about him dealing with the demons that he all but refused to acknowledge during his previous years. As such, Patrick Bateman's society was Ellis' society, regardless of how little he wanted to admit it back then.

American Psycho takes the irony of Bret Easton Ellis novels and turns it on its head a bit. It's also a further development of the novel version of The Rules of Attraction. In the novel The Rules of Attraction, Ellis explored multiple viewpoints through the use of multiple first person narrators. Many of these narrators were unreliable narrators, as they each had their own depiction of the same scene, each wildly different from each other. It's like Rashomon but over the course of a full year in college, and with constantly overlapping versions instead of one at a time.

American Psycho, however, takes more of its origins from Lolita or The Sound and the Fury, where it is completely first-person, using an unreliable narrator who also delves deep into his own personal fantasies without letting the reader know where the lines of his sanity is breaking. Reading American Psycho a second way required a bit of between-the-line reading.

Patrick Bateman is a complete loser in the novel. Nobody likes him, everybody hates him, and he doesn't like acknowledging it. His fiance is cheating on him very openly with one of his closest "friends." His drinking buddies constantly call him geek and dweeb for his constant repetition of "rules" from various fashion magazine memorizations, models ditch him at a moment's notice and seems bored to talk with him because he's so vacant. He can't get into Dorsia, but his "loser" brother, Sean Bateman can on a moment's notice.

Patrick Bateman is a loser. And, he is completely trying and failing to pose at life. All of his efforts at wearing the right clothes, reading the right magazines, watching the right shows, and using the right video stores are for naught. Even his mind-numblingly generic essays about popular bands are like amalgams from a Rolling Stone review, and half of them are so essentially wrong. Everybody thinks that he just hangs around taking up air. And, the constant acknowledgement of that pisses him off, because he doesn't have any real friends. Even his finace hates him. And, this resentment of the inability to be real and be popular boils into an anger.

This anger boils into flashes of violent fantasy. Every instance of violent fantasy in the novel is always cued by rejection and humiliation. He is rejected by his fiance, so he calls up a hooker to murder her. Bateman is passed over for a particular account, so kills the guy who got the account. It is very much that instant flash of "If only I could kill these people, then they would know who's boss."

The unreliability of the narrator couches all of this rejection in paragraphs and paragraphs of self delusion and narcissism. Much like Bateman can't see the forest for the trees, Ellis could barely see his own lifestyle even through his book. For the most part, he rejected the idea that he was the protagonist and that the book was completely about him. But, it wasn't until time, distance, and a more widespread acceptance of the novel had come to pass that Ellis really started coming out and admitting that the book was ultimately about his own unhappiness in the lifestyle that was totally Bateman.

The real meaning of American Psycho isn't about serial killers being able to pass in society. Patrick Bateman is no Benoit from Man Bites Dog. Even though Benoit's friends seem more scared of him than actually like him, Benoit is actually a killer who kills for purpose. Bateman is a coward. A dork, a geek, and a loser who takes all of his impotent rage out by fantasizing about killing people he deems unworthy. He never actually kills anybody. His fantasies are complete delusions. He's just massively unsatisfied.

The Movie (2nd pass)

"Certainly, I'm sure I explored a whole set of female fears in the film because the character is something that would be frightening to a woman. What could happen to you on a date, or that good-looking charming person turns out to be a monster. Men at their worst, what could they do to you." - Marry Harron, The Cinema Girl, circa 2000

Previously, I stated that American Psycho is a woman's point of view of the horror on screen. Mary Harron said that the horror of the book is the horror of a woman. These statements are only half correct.

Mary Harron recognizes that everybody thinks Bateman is a loser, and sets the film in his mind with his perception of who he is. The movie itself is more problematic than the book. A movie is harder to present other people's perceptions of Bateman as a geek and a loser when he is presented so immaculately and identically as everybody else that we are watching. He rarely slips into a status that is empty compared to everybody else because everybody else is just as empty.

We get reactions from people calling him a loser. He can't get into Dorsia. His business card isn't even up to snuff. His friends keep hanging out with him, and they rarely seem disturbed or annoyed by his actions. He isn't presented as a loser. And, thus, we're in a position that was initially presented with Rashomon. Since this is a movie with a completely unreliable narrator, to the point that his fantasies are completely surreal, can we assume that Bateman is a loser because occasionally the humiliations break through the shell of the movie? Or, can we assume that Harron was completely making a movie about the male psyche, and its danger towards women, and decided to make a horror movie because it was completely her fear.

Harron's quotes lean towards the latter, but the film is filled with enough inconsistencies to make it a more curious artifact up for discussion than one could get upon first viewing. The main problem is that one can relate to the characters calling Bateman a loser for completely different reasons than the ones that they're calling him loser for in the movie. Indeed, he could be a misunderstood hero in the movie.

Harron has laid the groundwork for the murders to be completely in Bateman's (and thus the narrator's) head. She has laid the groundwork for a reading that what you're watching isn't the full story, and you need to look deeper into the movie that's as much about surface as it is about deception and self-deception. Bateman the narrator could be lying to you. He lies (rather badly) to everybody else. Harron has Bateman saying things to the characters that should make people do spit takes or second glances but actually provoke no response. It could be taken as a critique of the obliviousness of his people, or their nonchalance towards violence. But, because of the unreliability of the narrator, one doesn't even know if he said them in reality, or just said it in his head. When he screams at a bartender how he wants to torture her, you don't know if he was saying that in his head and said he said it to make himself look good, or if her actually said it and nobody noticed.

Both the novel and the film are worth a look. The film is far less brutal than the novel, and it has far less interest in the banality of horror than the novel. It doesn't really want to say that violence is as boring and mundane as the novel is satirizing. And, it thus has a few different points. It also doesn't really plunge the male psyche as much as the novel, which completely engulfs the reader the first time and then stands off on subsequent reads.

No comments:

Post a Comment